By Yvette Campbell, Assistant Librarian, Special Collections & Archives

April Fools’ Day (April 1st) is a day often associated with misbehaving and tricking others into believing false stories or tales. The origins of the day, while complex, may have had their roots in pagan festivals marking the beginning of spring. The day evolved over centuries to become commonly affiliated with a trickster or jester figure who since medieval times has often been associated with inverting the social order and turning the world upside down.

Recently, I came across the names of two figures noted in the margins of two very different manuscripts in the Russell Library. Both figures have been associated with magic and trickery, and who in their own ways, were responsible for inverting the social order in their respective times: Simon Magus, the Magician and the Irish druid Mogh Ruith.

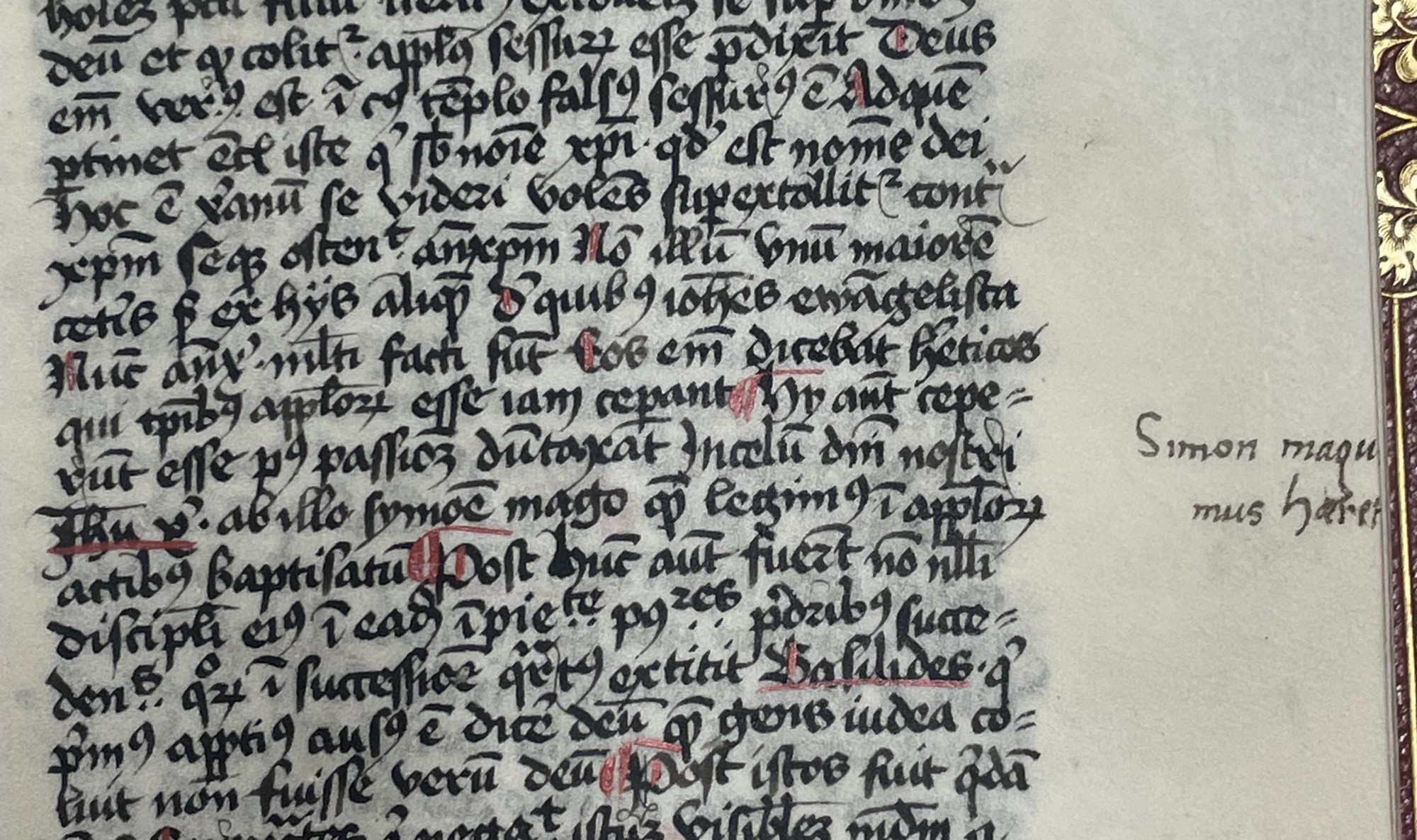

RB 71 is a medieval manuscript produced in the late 13th century by a single scribe. The Latin text contains works by St. Augustine. What caught my eye when cataloguing this item was a small annotation in the margins on fo.32r referring to a paragraph discussing Simon Magus.

Simon Magus (or Simon the Magician) was identified in Christian writings as a dangerous individual of the 1st century AD, who possessed great magical powers and attempting to trick followers of Christ into bestowing his powers to them in exchange for money and influence. He was challenged by St. Peter to change his ways and was universally acknowledged in ecclesiastical writings as the archetypal heretic of the Christian Church.

A former owner of RB 71 has annotated ‘SIMON MAGU-MUS HERET[IC]’ beside the paragraph in question. Medieval owners of such manuscripts often wrote in the margins of medieval manuscripts to draw attention to what they felt were important pieces of information. The margins were frequently left large enough in many scholastic texts to accommodate such annotations or glosses.

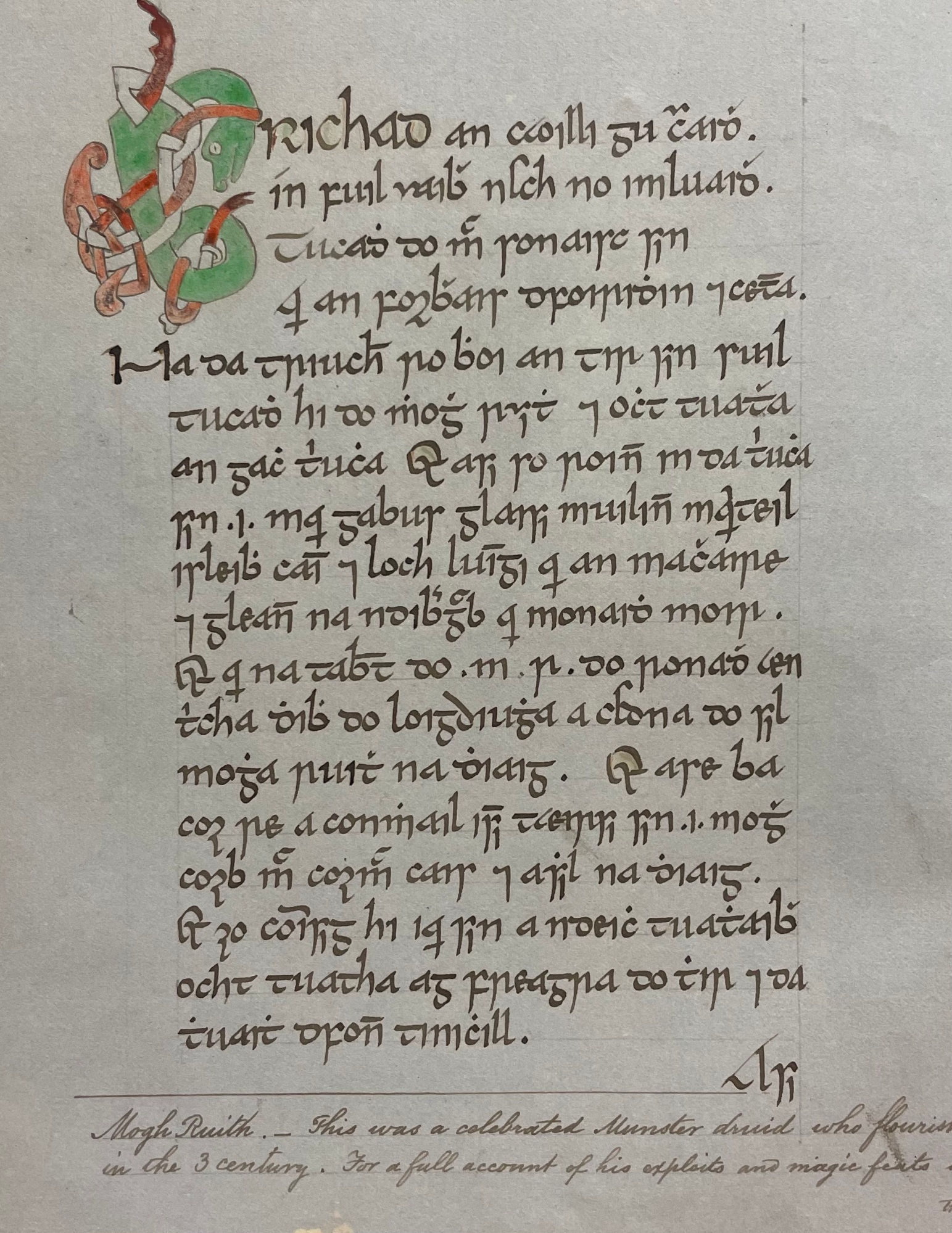

In comparison, PB 11 is a 19th century Gaelic manuscript originally from St. Colman’s College in Fermoy that similarly mentions another very famous magician in the margins – the legendary Irish druid known as Mogh Ruith (or Mug Ruith).

This Irish manuscript which was relocated to the Russell Library at Maynooth in 2013 was copied from the Book of Lismore (a late 15th century Gaelic manuscript) – in 1860 by Joseph Long of Whitechurch and gives a detailed account of the boundaries and history of Fermoy and its chieftains. It alludes to how the land was given to Mogh Ruith.

The annotation reads: “Mogh Ruith…was a celebrated Munster druid who flourished in the 3rd century. For a full account of his exploits and magic feats, see the Forbuis Dromdamhghaire [Forbhuis Droma Damhghaire] – a curious story of the reign of Cormac Mac Art.”

Mogh Ruith (“Slave of the Wheel”) was a formidable blind magician, sometimes compared to Merlin in Arthurian legend, who intervened in an epic magical conflict between Cormac Mac Art and Munster King Fiacha Muillethan at Knocklong. As soon as he bargained for a steep reward of land, the wizard used a spear to release the waters of Munster to drown Cormac’s rival druids and banished them from the land, turning some to stone with his breath of dark cloud. Cormac Mac Art felt like a fool for trusting the old pagan spirits of Ireland.

Wizards Unite : comparisons and contrast

Both magicians are based on legend with mythological elements – one recorded in the margins of a Gaelic manuscript and the other in the margins of a medieval Latin text; one in the Christian tradition and the other in pagan myths and legends with some overlap between the two figures.

In later tradition, Mogh Ruith was said to have travelled to the East to become a student under none other than…Simon Magus! It was claimed Simon Magus helped Mogh Ruith to build his famous flying machine called the roth rámach. According to the medieval Irish apocryphal tradition, Mogh Ruith was said to have been responsible for the beheading of St. John the Baptist.

Furthermore, in some Irish legends Simon Magus coincidentally came to be associated with druidism. The word ‘druid’ was sometimes translated into Latin as ‘magus’, and Simon Magus was said to be known in Ireland as Simon the Druid. By contrast, stories about Mogh Ruith are set in various periods of Irish myths with some tales placing him in Jerusalem at the dawn of Christianity under the tutelage of Simon.

While no fools themselves, these two trickster figures certainly succeeded in inverting the social order for a time, attempting to make fools of the people who chose to either follow or confront them. The similarities and overlap between the two have been shown, not least that two former owners’ – centuries apart – highlighted their names in the margins of two completely different manuscripts in our collection – a perfect comparison for April Fools’ Day!

For access to our manuscript collections and other materials for consultation, please make an appointment with us by emailing Library.Russell@mu.ie or phoning (01) 708 3890

Further reading:

Shingurova, Tatiana (2018). The Story of Mog Ruith: Perceptions of the Local Myth in Seventeenth-Century Ireland. Proceedings of the Harvard Celtic Colloquium, Vol. 38., pp. 231-258