by Pádraig Ó Macháin Professor of Modern Irish at University College Cork.

The work of the IRC-funded and UCC-based Inks and Skins project is focused on the Irish manuscript of the vernacular Gaelic tradition from 1100 to 1600. It seeks to provide scientific answers to ostensibly simple questions such as: what inks and pigments did the Gaelic scribes use? What can analysis of vellum tell us about production, preparation and use of these great books? Was there a difference between these materials and those used in manuscripts from the early Church tradition in Ireland, or from parallel traditions elsewhere in Ireland and abroad?

One of these parallel traditions is that of religious manuscripts produced in continental Europe in the late medieval period. To form a general idea of the materiality of these books, Inks and Skins, through the kindness of the wonderful staff in Special Collections, availed of the opportunity to carry out analysis on selected manuscripts from the medieval collection in the Russell Library, Maynooth University. Most of these manuscripts were written in the Low Countries and in France during the late-medieval period; a few are near-contemporaries of the project’s target manuscript, the Book of Uí Mhaine, written in Co. Galway in the second half of the 14th century.

The Maynooth medieval collection is in the happy position of having been the subject of an excellent and thorough catalogue: that of Peter and Angela Lucas, published in 2014. The catalogue provides detailed information on provenance, divisions of hands, scripts, decoration, collation and contents. It is an exemplary piece of work, and a must-have for anyone with even a cursory interest in the hand-made book. For Inks and Skins, the Lucas catalogue greatly facilitated the selection of targets that aligned with the time-frame of our work.

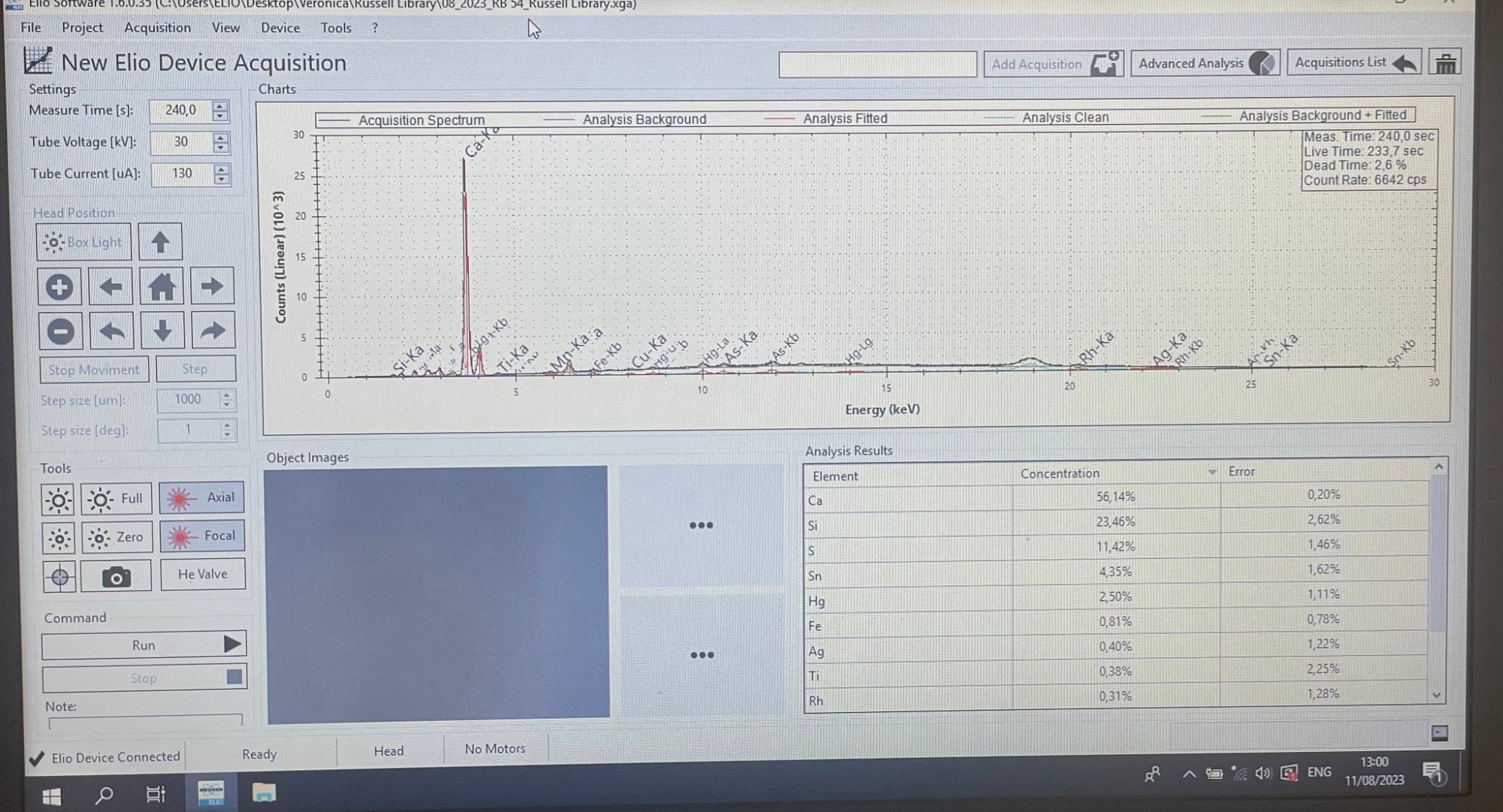

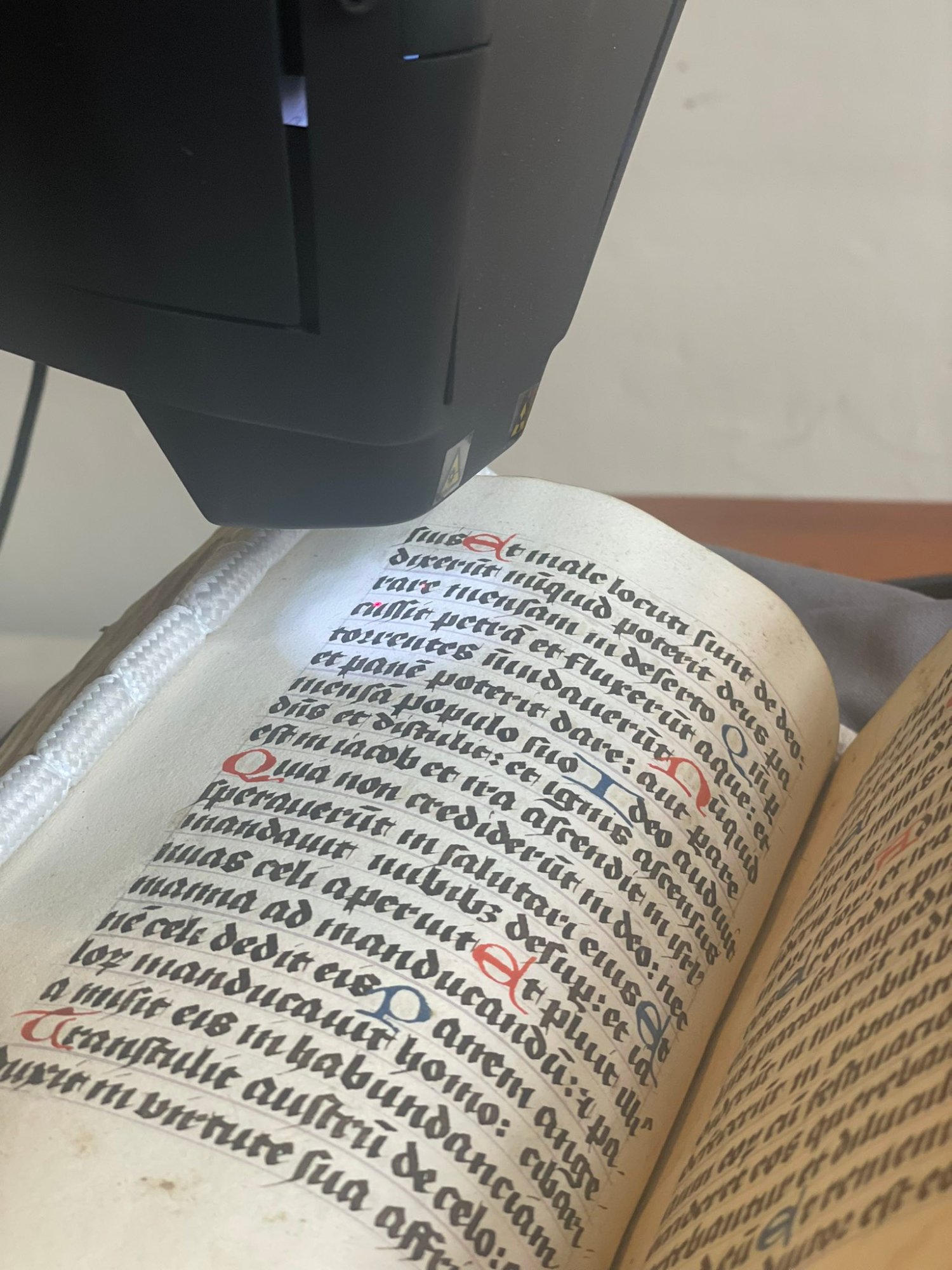

That work consisted of X-Ray Fluorescent spectroscopic analysis combined with optical microscopic investigation and photography, over the period of a week in August 2023, of the inks and pigments in eight manuscripts of the collection, dating from the 12th to the 16th century. These manuscripts included bibles, psalters, books of hours, and a benedictional. They presented a variety of scripts and textual arrangements on calfskin and, in one instance, sheepskin. Skin thicknesses ranged from .1 to .26 mm.

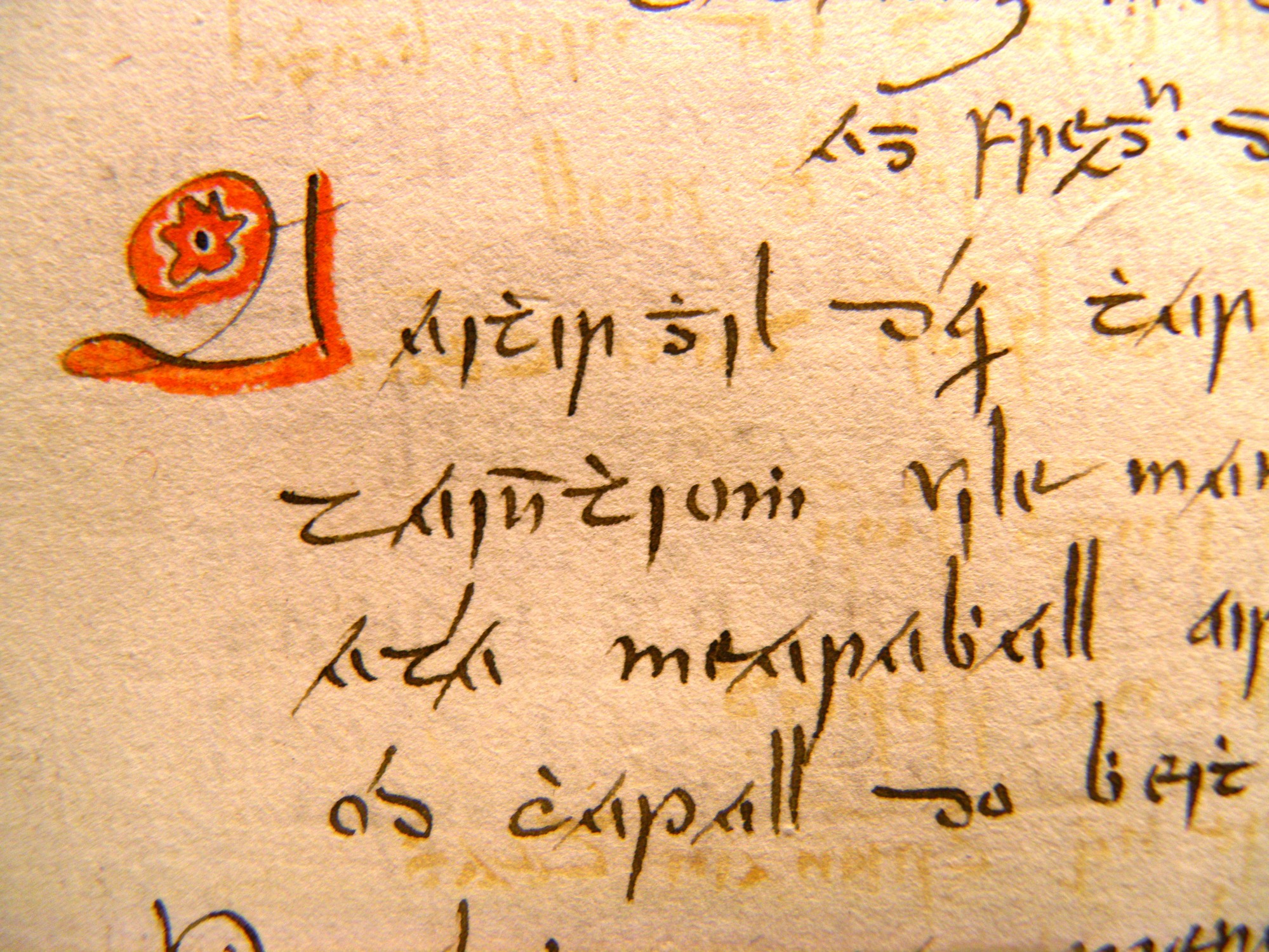

The decoration of these manuscripts came in a variety of styles and materials – the colour palate particularly – not present in their Gaelic contemporaries, obviously so in the case of the Books of Hours, which, in addition to letter and page decoration, involved the contribution of miniaturists who created the full-page illustrations. Another over-riding difference between the two traditions is the simple one of the clarity and cleanliness of the mainland European books, which were stored in libraries almost from the moment of their creation, in contrast to the Gaelic manuscripts, which never saw the inside of libraries until centuries later, and consequently bear all the marks of having ‘slept rough’ for a long number of years.

Despite material differences between the continental manuscripts and those of the Irish vernacular tradition, their shared heritage of bookcraft is plain to see, from quiring and ruling to the use of different grades of litterae notabiliores to signify the beginning of texts and sections of texts. The dominance of iron gall-ink is also part of this shared heritage, as is the distinction between the public and the personal book, defined by portability: the folio-sized bible or psalter as opposed to the pocket-sized personal prayerbook.

These results help us to better understand the Gaelic vernacular, insular tradition as a variant within a common heritage of bookcraft that extends back to early Christian times, when writing and the art of the manuscript were first introduced to Ireland.